The monetary policy of the RBA seems to have had little impact on inflation and the rate of unemployment over the period since 2002 – in fact, the impact seems to have been perverse. That is, the opposite of what was intended! Unless the RBA recognizes this, they run the risk of pushing interest rates up far too high and for too long.

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) belatedly embarked on a program of lifting interest rates in May 2022, to quell high inflation in Australia. Inflation has become a global problem and Central Banks in many countries have also been lifting interest rates with the same objective. The plan is for higher interest rates to reduce demand in the economy so that companies have to lower prices, or at least hold them steady, to minimize loss of sales.

Of concern to the RBA is the possibility of a wage-price spiral, in which workers demand higher wages to counter higher prices and companies lift prices to pay higher wages.

Economists have a theoretical concept called NAIRU, an acronym for non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment. According to the RBA:

“The NAIRU is the lowest unemployment rate that can be sustained without causing wages growth and inflation to rise. It is a concept that helps us gauge how much ‘spare capacity’ there is in the economy. The NAIRU cannot be observed directly. However, we can infer things about the NAIRU from other variables that can be observed, and which give clues about the level of spare capacity in the economy”.

“There are different ways to estimate the NAIRU, using various statistical models. While the true value of the NAIRU cannot be known, and any estimate has a range of uncertainty around it, research by the Bank pointed to the NAIRU for Australia being below 5 per cent prior to the COVID-19 pandemic”.

If the unemployment rate is lower than the NAIRU, according to this theory, the economy is operating above its full capacity, and there is upward pressure on inflation. If inflation is likely to be above the Board’s target, the Reserve Bank Board might want to cool the economy by raising the cash rate target and/or withdrawing other policy support. This would help to reduce aggregate demand and inflationary pressures.

Conversely, If the unemployment rate is higher than the NAIRU, the economy would not be at full employment and there would be downward pressure on inflation. If inflation is likely to be below the Board’s target, the Reserve Bank Board might want to stimulate the economy by lowering the cash rate target and/or implementing unconventional policies. This would encourage spending, thereby stimulating aggregate demand and reducing spare capacity.

But do higher or lower interest rates actually impact the unemployment rate? Recent history would suggest the answer is no!

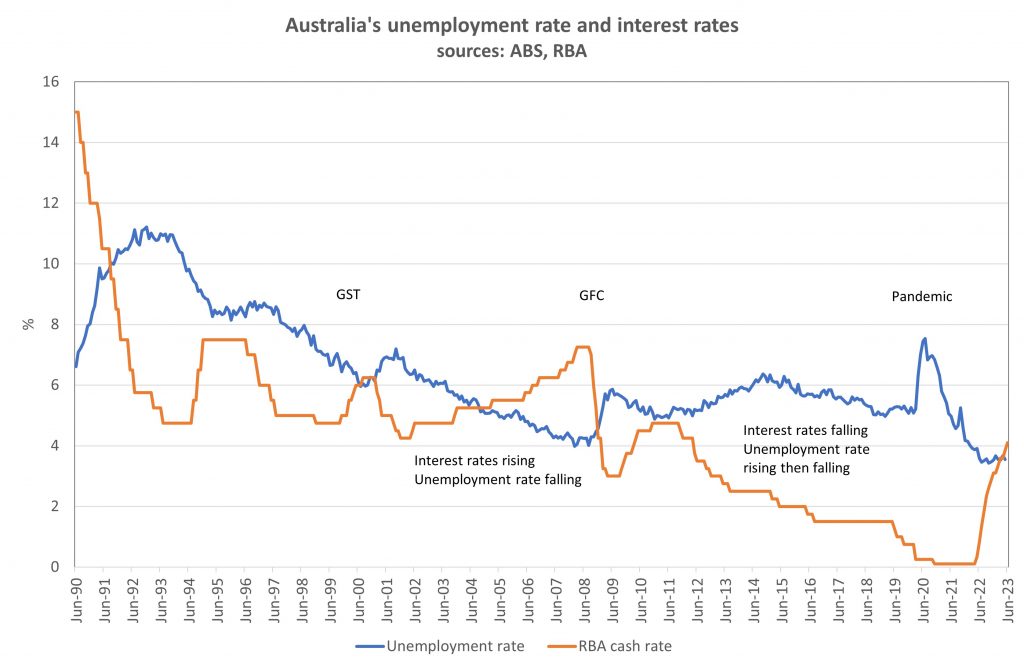

The chart shows the relationship between interest rates and the unemployment rate.

Between May 2002 and March 2008, Australia’s unemployment rate was falling so the RBA was lifting interest rates. But the unemployment rate continued to fall! This is contrary to the theory that raising interest rates will cool the economy and the unemployment rate will rise. Interest rates do act with a lag, but not a lag of over six years. It was the global financial crisis, which economists did not foresee, which caused the unemployment rate to rise.

The RBA was cutting interest rates between November 2011 and October 2019, before cutting again during the pandemic. Over the November 2011 to October 2019, the unemployment rate changed from 5.2% to 5.3%. Effectively no change. Despite interest rates hitting a record low. This is contrary to the theory that lowering interest rates will stimulate the economy and cause the unemployment rate to fall. The RBA estimated that NAIRU was 5% in late 2019, but never succeeded in getting the unemployment rate below that figure by early 2020.

The RBA is predicting that with the steep rise in interest rates since May 2022, the unemployment rate will rise to 4.5% by late 2024. This may well happen, but the recent past casts doubt on this prediction.

The industry composition of employment has changed dramatically since the 1980’s and 1990’s. Interest rate sensitive industries such as manufacturing and retail sales employ a much lower proportion of the workforce: manufacturing has fallen from 11.5% to 6.5% of employment between 2002 and 2023 and retail has fallen from 11.4% to 9.3% over the same period. Industries where employment growth has been highest are not interest rate sensitive: health care and social assistance has increased from 9.8% to 15.3% of total employment between 2002 and 2023. Professional services (including scientific and technical) and education & training have both increased their shares of total employment significantly over this period.

Do higher interest rates reduce price inflation?

Between the June 2002 and March 2008 quarters, the RBA was lifting interest rates (the cash rate went from 4.5% to 7.25%). Over that period, the annual change in the CPI went from 2.8% to 4.3%. Not what would have been expected! The inflation rate of 4.3% after all those interest rate hikes, was above the RBA target rate of 2% to 3%!

Between the December 2011 quarter and the December 2019 quarter, the RBA was cutting interest rates, from 4.5% to 0.75%. Over that period, the annual change in the CPI went from 3.0% to 1.8%. The inflation rate of 1.8% after all those interest rate cuts, was below the RBA target rate of 2% to 3%!

The monetary policy of the RBA seems to have had little impact on inflation and the rate of unemployment over the period since 2002 – in fact, the impact seems to have been perverse. That is, the opposite of what was intended! Unless the RBA recognizes this, they run the risk of pushing interest rates up far too high and for too long.

Maybe this time will be different. There have been signs of a significant slowdown in consumer spending growth since the December 2022 quarter, which may worsen given the interest rate increases since then. But will slowing the economy to the point of recession lift the unemployment rate significantly and return price inflation back to the 2% to 3% target range? We can’t count on it.

The RBA is required to achieve full employment, as well as keeping inflation in a narrow band. How close are we to that goal now?

Between June 2022 and May 2023, the unemployment rate has averaged 3.6%, the lowest in over 40 years. On that measure, we are closer to full employment now than we have been since the 1970’s.

Another measure is underutilization, which adds the number of people who would like to work more hours (underemployed) to the number of people unemployed. The underutilization rate has recently increased, from 9.4% in late 2022 to 10.0% in May 2023.

The number of people unemployed is 516,000 and the number underemployed is 937,000. Together, this is 1.453 million people who are underutilized. To be counted as unemployed, a person has to look for work and be available to start work immediately. There are another 767,000 who did not look for work but who would be available to start within four weeks (most were available to start immediately). Thus, there are well over 2 million people who are either unemployed, underemployed, or are potential workers.

We are clearly a long way from full employment, despite a very low unemployment rate and despite employers complaining about shortages of skilled workers.